Section C. Military Risk in Wars, 2025 Global Survival Rank (GSR) by Dr. Ziva Rozen-Bakher

https://www.rozen-bakher.com/gsr/2025/c/military-risk

Published Date: 12 October 2025

COPYRIGHT ©2022-2025 ZIVA ROZEN-BAKHER ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Global Survival Rank (GSR) by Dr. Ziva Rozen-Bakher: Yearly Rank to Compare the Global Political Power among Countries, Alliances and Coalitions to Survive Long Wars at the Military, Economic, and Political Levels

Rozen-Bakher, Z. Global Survival Rank (GSR) by Dr. Ziva Rozen-Bakher https://www.rozen-bakher.com/gsr

Rozen-Bakher, Z. 2025 Global Survival Rank (GSR) by Dr. Ziva Rozen-Bakher, 2025 Global Survival Rank (GSR) by Dr. Ziva Rozen-Bakher, 12 October 2025, https://www.rozen-bakher.com/gsr/2025

Rozen-Bakher, Z. 2024 Global Survival Rank (GSR) by Dr. Ziva Rozen-Bakher, 2024 Global Survival Rank (GSR) by Dr. Ziva Rozen-Bakher, 30 April 2024, https://www.rozen-bakher.com/gsr/2024/e

Rozen-Bakher, Z. 2023 Global Survival Rank (GSR) by Dr. Ziva Rozen-Bakher, 2023 Global Survival Rank (GSR) by Dr. Ziva Rozen-Bakher, 29 April 2023, https://www.rozen-bakher.com/global-survival-rank-zrb/2023

Dr. Ziva Rozen-Bakher

Researcher in International Relations and Foreign Policy with a Focus on International Security alongside Military, Political and Economic Risks for Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and International Trade

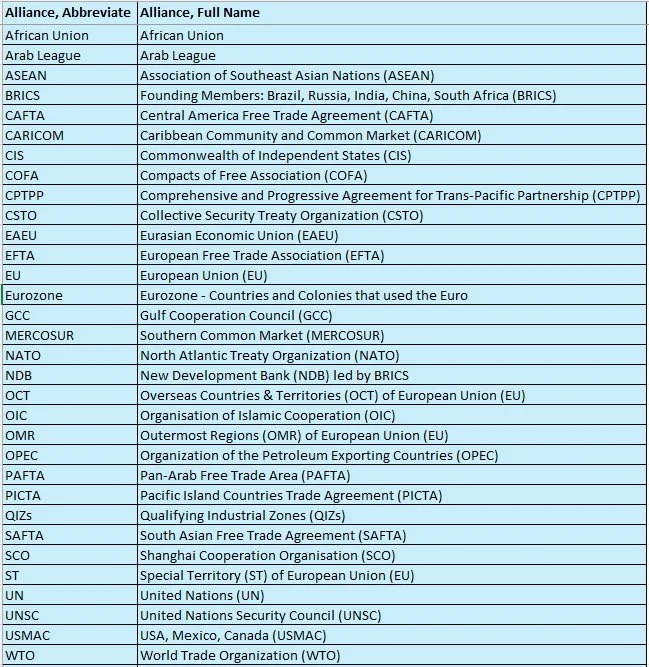

List of Multilateral Alliances Included in 2025 Global Survival Rank (GSR), Full Name and Abbreviation

Section C. Military Risk in Wars, 2025 Global Survival Rank (GSR) by Dr. Ziva Rozen-Bakher

For More Information about Various Multilateral Military Defence Treaties (MMDT) and Bilateral Military Defence Treaties (BMDT):

Military Alliances Led by Russia and China, Monitoring Alliances by Dr. Ziva Rozen-Bakher, https://www.rozen-bakher.com/alliances/rcm

Military Alliances Led by USA, Monitoring Alliances by Dr. Ziva Rozen-Bakher, https://www.rozen-bakher.com/alliances/usa-military

Section C - List of Contents

Section C. Military Risk in Wars, 2025 Global Survival Rank (GSR) by Dr. Ziva Rozen-Bakher

Section C1. Typology of Military Defence Alliances

Section C1.1 Multilateral Military Defence Treaty (MMDT) versus Bilateral Military Defence Treaty (BMDT)

Section C1.2 Military Defence Treaty with Two-Directions (TD) versus Treaty with One-Direction (OD)

Section C1.3 Active Military Defence Treaty versus Inactive Military Defence Treaty

Section C1.4 Military Support Treaty versus Military Defence Treaty

Section C1.4.1 Military Support Treaty

Section C1.4.2 Military Defence Treaty

Section C1.4.2.1 Military Defence Treaty with a 'Clear Commitment' to Defend in the Case of an Attack: 'Hard-Definition' versus 'Mid-Definition' versus 'Soft-Definition'.

C1.4.2.1.1 'Hard-Definition'

C1.4.2.1.2 'Mid-Definition'

C1.4.2.1.3 'Soft-Definition'

Section C1.4.2.2 Military Defence Treaty with an 'Unclear Commitment' to Defend in the Case of an Attack

Section C2. Military Cooperation under Multilateral Trade Alliances

Section C3. Foreign Military Presence in Host Countries: Trade-off between Military Benefits and Military Risks

Section C1. Typology of Military Defence Alliances

Military Defence Alliances are exist from the early days of modern humanity, and we still have active Military Defence Alliances that were signed in the Middle Ages, such as the oldest active Military Defence Alliance between England and Portugal that was signed in 1373. However, over the centuries Military Defence Alliances evolved into more complex alliances in terms of typology and definitions, so it’s important to distinguish between the different types of Military Defence Alliances, as follows:

Section C1.1 Multilateral Military Defence Treaty (MMDT) versus Bilateral Military Defence Treaty (BMDT)

First, it is important to distinguish between a Multilateral Military Defence Treaty (MMDT) that includes more than two countries versus a Bilateral Military Defence Treaty (BMDT) that includes only two countries. NATO and CSTO are good examples for MMDT, while the China-North Korea Treaty and the USA-Japan Treaty are good examples for BMDT.

Section C1.2 Military Defence Treaty with Two-Directions (TD) versus Treaty with One-Direction (OD)

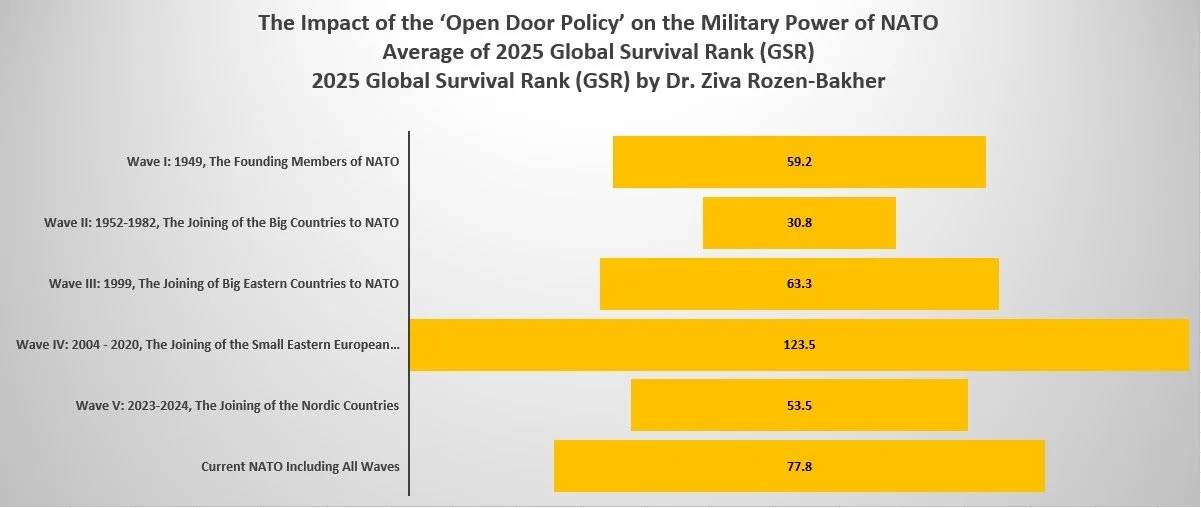

Second, it is also important to distinguish between Military Defence Treaty with Two-Directions (TD), where both sides commit to Defend in the case of an attack (e.g., the USA-Canada Treaty) versus Treaty with One-Direction (OD), where only the ‘Strong Country’ has the commitment to Defend its ‘Weak Ally’, while the ‘Weak Ally’ has no commitment to defend the ‘Strong Country’, such as the China-Solomon Islands Security Pact or the USA-Japan Treaty. Usually, a Multilateral Military Defence Treaty (MMDT) is based on a Defence Treaty with Two-Directions (TD), such as the CSTO. Although NATO is a good example of MMDT that started as a Treaty with Two-Directions (TD), namely the majority of the members in Wave I to Wave III, were relatively equal, as shown in Chart 15 below. However, the ‘Open Door Policy’ of NATO via Wave IV makes NATO more like a Treaty with One-Direction (OD) because too many members are weak ones, while only several members are strong ones, as shown in Chart 16 below. Nevertheless, most of the Bilateral Military Defence Treaties (BMDT) are Treaties with One-Direction (OD) that even restrict the treaties to a specific regional area, such as the USA-Japan Treaty.

Chart 15. Impact of the ‘Open Door Policy’ on the Military Power of NATO: Joining Waves by Average of 2025 Global Survival Rank (GSR)

For Full Details, Please see Section E26.4 in Section E26. NATO - Multilateral Military Defence Treaty (MMDT): North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), 2025 Global Survival Rank (GSR) by Dr. Ziva Rozen-Bakher https://www.rozen-bakher.com/gsr/2025/e/nato

Chart 16. Impact of the ‘Open Door Policy’ on the Military Power of NATO by Strong/Weak/Very Weak NATO Members, Total and Average of 2025 Global Survival Rank (GSR)

Section C1.3 Active Military Defence Treaty versus Inactive Military Defence Treaty

Third, there is a big difference between Active Military Defence Treaty versus Inactive Military Defence Treaty. Many old Military Defence Treaties are de-facto Inactive Treaties due to reasons such as regime transformation, political circumstances, and changes in geopolitical order, as well as because of new leaders that oppose the treaties that were signed by former leaders, or vice versa, due to collaboration with new allies that are considered as rivals to the treaty. The Multilateral Military Defence Treaty (MMDT), the Rio Pact, is a good example of how a treaty over the years becomes an inactive treaty. The Rio Pact was signed in 1947, but currently at the formal level, it includes the USA and 17 countries from Latin America. However, the Rio Pact is an inactive treaty because the Alliance does not conduct yearly summits nor joint-drills. Importantly, the Rio Pact as an MMDT has no Active Headquarter like the Active Headquarters that exist in NATO, CSTO, and Peninsula Shield Force (PSF) of the GCC, yet keep in mind that an ‘Active Headquarter’ is usually relevant to MMDT and less to BMDT. Furthermore, over the years, many members of the Rio Pact have distanced themselves from the treaty, so if, for example, a war erupts between the USA and Russia, then it's unlikely that Brazil and Venezuela will be involved in a war against Russia to protect the USA, despite that Brazil and Venezuela being formal members of the Rio Pact. Hence, the 2025 Global Survival Rank (GSR) does not take into account Inactive Military Defence Treaties, but only Active Military Defence Treaties.

Section C1.4 Military Support Treaty versus Military Defence Treaty

There is a crucial difference between a Military Support Treaty versus a Military Defence Treaty, as presented in this section.

Section C1.4.1 Military Support Treaty

Military Support Treaties are usually Bilateral Treaties, rather than Multilateral Military Treaties. A Military Support Treaty aims to give support via Military Aid in the case of an attack but without the commitment to defend in the case of an attack, so the country needs to fight alone with its army in wars, yet with the hope of getting any Military Aid during the wars. More specifically, in a Military Support Treaty, there is no commitment to give the Military Aid, but a declaration of intent to support via Military Aid in the case of an attack because the scope of the Military Aid depends on the ability to give the support at a certain time of the attack based on the economic and political circumstances. In other words, the amount of the Military Aid depends on the yearly budget of Military Aid that the country has, alongside IF it is going to be approved by the parliament, and if yes, WHAT is going to be the amount of the Military Aid. Thus, it is possible that a country under an attack will get only a small amount of Military Aid or even will not get a Military Aid at all, despite that the country has a Military Support Treaty, which may occur especially in situations whan there are several wars in-parallel, or a World War, in particular. For example, the USA has numerous Bilateral Military Support Treaties that the USA has with its Allies, but each time when the USA needs to give a Military Aid based on one of these Bilateral Military Support Treaties, then the Military Aid should be approved by the USA’s Senate, including the amount of the Military Aid. Thus, in some cases, it is approved by the USA’s Senate and sometimes not (Cite 1), depends on the USA’s budget for Military Aid alongside the geopolitical interests of USA, and importantly, who has the majority in the USA’s Senate, the Republicans or the Democrats (Cite 2). Considering the above, the 2025 Global Survival Rank (GSR) does not take into account Military Support Treaties because of the lack of commitment to defend in the Case of an Attack, resulting in the lack of Military Backup during wars, as well as because of the lack of a definite commitment to get a Military Aid in the Case of an Attack, which does not for sure reduce the Military Risk in long wars.

Section C1.4.2 Military Defence Treaty

A Military Defence Treaty is a treaty with a commitment to defend in the case of an attack. There are many Multilateral Military Defence Treaties (MMDT) that most of them are with 'Two-Directions (TD)', as well as many Bilateral Military Defence Treaties (BMDT), either with 'Two-Directions (TD)' or with 'One-Direction (OD)'. Still, there are many Inactive Treaties among the oldest Military Defence Treaties. Importantly, there are even Multilateral Military Defence Treaties (MMDT) that have even a Joint-Force, such as the Peninsula Shield Force (PSF) of the GCC, as well as the African Standby Force (ASF) of the African Union (AU).

However, the most critical issue in a Military Defence Treaty is if the treaty has a clear commitment to defend in the case of an attack or, vice versa, an unclear commitment. That’s because a clear commitment impacts in a critical way the Militery Backup of the country in wars, resulting in a lower Military Risk, while an unclear commitment, resulting in a lack of Militery Backup in wars that significantly increases the Military Risk of a country, especially in long wars. From a historical perspective, a Military Defence Treaty always has a clear commitment to defend in the case of an attack, but since the 20th century, when the law evolved into a sophisticated manner, the Military Defence Treaties have also become more sophisticated and complicated in terms of the definition regarding the commitment to defend in the case of an attack. Importantly, after WWII, on the one hand, more Military Defence Treaties were formed, but on the other hand, many of them included an unclear definition about the commitment to defend in the case of an attack to avoid direct involvement in wars. It can be argued that the 'Cold War' led to a 'Competition of Military Imperialism' in a way that each superpower or prominent country had the objective to show-off that it had many Military Defence Treaties. Although, to reduce the risk of this 'Tsunami of Military Defence Treaties', then the 'Commitment to Defend in the Case of an Attack' started to become less clear to avoid as much as possible direct involvement in wars. Alternatively, it could be argued that some Military Defence Treaties were formed without a real intention to defend in the case of an attack, which led to a sophisticated definition, namely to an unclear commitment in trying to hide that there is no intention to defend in the case of an attack.

Section C1.4.2.1 Military Defence Treaty with a Clear Commitment to Defend in the Case of an Attack: 'Hard-Definition' versus 'Mid-Definition' versus 'Soft-Definition'

When we speak about a Military Defence Treaty, it is crucial to distinguish between a treaty with a 'Clear Commitment' to defend in the Case of an Attack versus a treaty with an 'Unclear Commitment' to defend in the Case of an Attack. Nevertheless, there are three levels of definition that can be considered as a 'Clear Commitment' to Defend in the Case of an Attack, as presented in this section.

C1.4.2.1.1 'Hard-Definition'

A 'Hard Definition' usually includes the following kind of definition: 'An attack against one member of the treaty will be considered as an attack against all members of the treaty', resulting in a situation in which all the members of the treaty commit to join the war to defend the member that suffers from the attack. NATO and CSTO are good examples of MMDTs with a 'Hard-Definition'’ of a clear commitment to defend in the case of an attack, while the USA-Japan Treaty and the China-North Korea Treaty are good examples of BMDTs with a ‘Hard-Definition’ of a clear commitment to defend in the case of an attack. The saga of the Russia-Ukraine War that erupted due to the wish of Ukraine to join NATO is a very good example of the importance of the 'Hard Definition' of commitment to defend in the case of an attack as exists in NATO, because if Ukraine joins NATO it will give Ukraine a 'Military Backup' in the case of a war against Russia (Cite 3). Thus, it's no surprise that Russia opposes it in a hard way because Ukraine is like the 'Gateway' to Moscow (Cite 4).

C1.4.2.1.2 'Mid-Definition'

The main difference between 'Hard-Definition' and 'Mid-Definition' is in the 'Consultation' before the activation of the treaty, namely under 'Hard-Definition', there is no need for 'Consultation' before joining the war to defend the member that suffers from the attack, while under 'Mid-Definition', in the case of an attack, the parties to the treaty will carry out a 'Consultation' about the need to join the war to defend the member that suffers from the attack. The China-North Korea Treaty versus the China-Russia Treaty is a good example of 'Hard-Definition' versus 'Mid-Definition. The China-North Korea Treaty is a 'Hard-Definition' treaty, namely “the two nations undertake all necessary measures to oppose any country or coalition of countries that might attack either nation”, so under this treaty there is a commitment to defend each other without the need for 'Consultation' (Cite 5). However, the China-Russia Treaty is a 'Mid-Definition' treaty, namely ”When a situation arises in which one of the contracting parties deems that peace is being threatened and undermined or its security interests are involved or when it is confronted with the threat of aggression, the contracting parties shall immediately hold contacts and consultations in order to eliminate such threats”. That means that in the case of an attack against Russia or China, the two countries will immediately conduct a consultation to eliminate the threat, namely the consultation aims to check if the country can eliminate the threat alone or if the country needs help to eliminate the threat via joint defence. Hence, Russia and China have a Military Defence Treaty under a Clear Commitment to defend each other in the case of an attack, yet the treaty takes into account that both countries, Russia and China, are Big and Strong Countries that can eliminate many external threats alone, and because of that comes the consultation to understand if under a certain attack help is needed to eliminate the threat or not. Therefore, if a significant attack occurs against Russia and China, then both countries will act together to eliminate the threat via a joint counter-offensive (Cite 6).

C1.4.2.1.3 'Soft-Definition'

'Soft-Definition' treaty lays down the ‘Backdoor’ for the Commitment to Defend in the Case of an Attack. The China-Solomon Islands Security Pact is a good example of BMDT with One-Direction (OD) under a 'Soft Definition'. First, the Security Pact between China and the Solomon Islands includes a commitment from China to send military forces in the case of 'Political Instability' in the Solomon Islands (e.g., coups or riots), so an external attack is obviously 'Political Instability', which also justifies sending military forces to calm down the 'Political Instability'. Second, the Security Pact allows China Naval to use the Solomon Islands as a ‘Military Station’, and China has the right to defend its assets and military personnel in the Solomon Islands under ‘external threat’, so in the case of an attack against the Solomon Islands, China will protect the Solomon Islands in order to protect its assets and military personnel in the Solomon Islands, resulting in a Clear Commitment to defend the Solomon Islands under an external attack (Cite 7).

In light of the above, in spite of the differences between the types of definitions, the outcome in wars under - 'Hard-Definition' or 'Mid-Definition' or 'Soft-Definition' - is going to be the same, namely the parties to the Military Defence Treaty will join the war to defend the member that suffers from the attack. Thereby, all the types of definitions mentioned above are included under a ‘Clear Commitment to Defend in the Case of an Attack’. Hence, the 2025 Global Survival Rank (GSR) includes all the MMDTs and BMDTs worldwide that have a ‘Clear Commitment to Defend in the Case of an Attack’, either under Hard-Definition or Mid-Definition or even Soft-Definition.

Section C1.4.2.2 Military Defence Treaty with an 'Unclear Commitment' to Defend in the Case of an Attack

The main difference between Military Defence Treaties with 'Clear Commitment' versus 'Unclear Commitment' is the 'Conditions' that the treaty includes in order to defend in the case of an attack, so it is unclear if all the conditions will be fulfilled in order to activate the treaty. The USA–Philippines Treaty is a good example of BMDT under 'Unclear Commitment' because the treaty has too many pre-conditions that should be fulfilled before any act of mutual defence, as shown in Document 1. below. Anyway, the treaty focuses only on the pacific region, so the Philippines has no commitment to defend the USA in the case of an attack on USA soil but only in the case of an attack on USA territories in the pacific. Hence, it can be argued that the big difference between 'Soft-Definition' and 'Unclear Commitment' is the 'intention to defend' versus 'an attempt to avoid intervention' in the case of an attack. In the 'Soft-Definition' treaty, there is intention to defend in the case of an attack, but due to political reasons, a 'Soft-Definition' is needed in the style of ‘Backdoor’ for intervention in war, likely to defy internal and external criticism against the Military Defence Treaty. However, in the 'Unclear Commitment' treaty, there is an attempt to avoid intervention in wars via the pre-conditions that serve as safeguards from direct involvement in wars. Considering the above, the 2025 Global Survival Rank (GSR) does not take into account Military Defence Treaties with an 'Unclear Commitment' to defend in the case of an attack because such kinds of treaties did not definitely give Military Backup during wars, resulting in an increase in the Military Risk in long wars.

Document 1. Mutual Defense Treaty Between the United States and the Republic of the Philippines, 30 August 1951

Cite 1. Senate Blocks $14.3 Billion Israel Aid Bill | National Review, National Review, 14 November 2023

Cite 2. Record Number of Senate Democrats Vote to Block Weapons Sales to Israel, Jewish Exponent, 01 August 2025

Cite 3. Ukraine Can't Join NATO While at War with Russia, The National Interest, 24 June 2024

Cite 4. Putin would demand Ukraine never join NATO in any Trump talks, Detroit News, 15 January 2025

Cite 5. China-N. Korea defense treaty, The Korea Times, 26 July 2016

Cite 6 Russia, China declare friendship treaty extension, hail ties AP, 28 June 2021

Cite 7. Solomon Islands Leader Defends New Security Pact With China, News On 6, 20 April 2022

Section C2. Military Cooperation under Multilateral Trade Alliances

Military Cooperation exists between countries at various levels without forming any military alliance. However, Military Cooperation under Multilateral Trade Alliances sometimes can be considered as an 'Informal Military Alliances'. More specifically, many Trade Alliances, including Economic and Political Alliances, have some level of a Military Cooperation, such as Arms Exports, Intelligence-Sharing, and Military Training. Still, when a Multilateral Trade Alliance has a Formal Military Cooperation that includes Security Summits and Joint Drills as in the case of SCO and BRICS, then it may look like as 'Informal Military Alliances'. Nevertheless, we should keep in mind that these 'Informal Military Alliances' have no any commitment to defend in the case of an attack, while not all the members are active in the Joint Drills, as in the case of BRICS. In spite of that, a group of Multilateral Trade/Economic/Political Alliances that have shared interests at the political and military levels may form an 'Informal Military Alliance' or even a 'Formal Military Alliance' during long wars. Thus, these 'Informal Military Alliances' can give an indication for the Blocs or Coalitions that may be formed in the case of World War or even in the case of a significant regional war. For example, if we are mapping the current Multilateral Trade/Economic/Political Alliances, then BRICS, SCO, and CIS, likely will act together as a 'Counter-NATO' during a significant regional war or World War, excluding members that may be 'Sitting on the Fence’. Considering the above, the 2025 Global Survival Rank (GSR) does not take into account 'Informal Military Alliances' because this 'Informal Mechanism' does not promise any Military Backup’ nor reduce the Military Risk, but only gives an indication of the potential of creating military alliances in a significant long war.

Section C3. Foreign Military Presence in Host Countries: Trade-off between Military Benefits and Military Risks

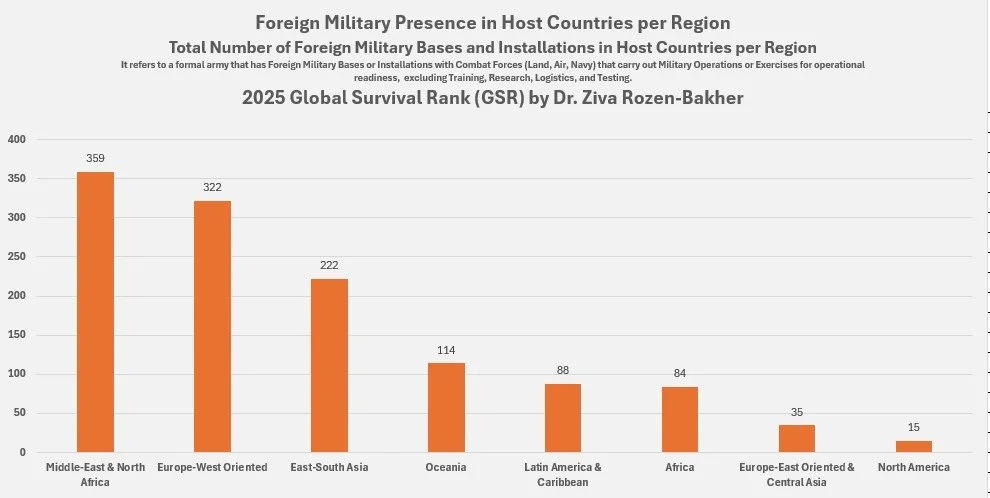

Foreign Military Presence in Host Countries gives an important layer about the Military Backup and Military Risk that a Host Country has when Foreign Military bases and installations are located in the host country (see Chart 17 below) or, vice versa, when a Home Country has multiple Host countries with Foreign Military Presence (see Chart 18 below).

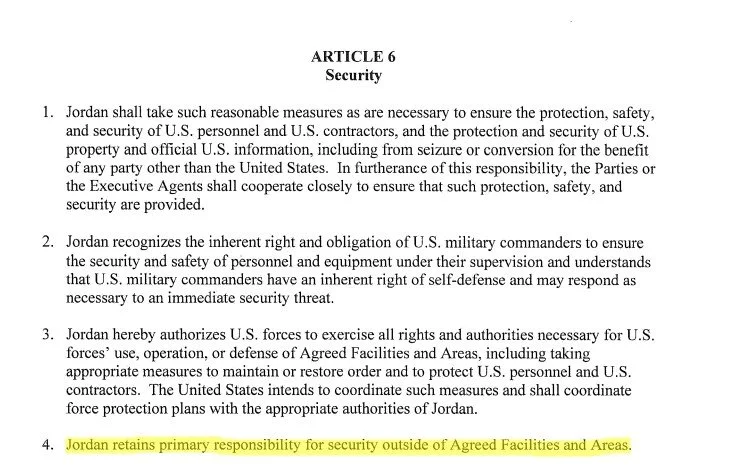

From the Host Country perspective, there is a Trade-off between the Military Benefits and the Military Risks regarding Foreign Military Presence. On the one hand, Foreign Military Presence gives some Military Backup to the host country, but on the other, Foreign Military Presence is not a Military Defence Treaty, so paradoxically, it does not promise any commitment to defend in the case of an attack. The agreement between the USA and Jordan about the USA’s Foreign Military Presence in Jordan is a good example of that (Cite 8). More specifically, according to Article 6 on Security from the USA-Jordan agreement (see Document 2 below), not only that the USA have no commitment to defend Jordan in the case of an attack, but the opposite, Jordan should defend the USA’s personnel and installations in Jordan (see Clause 1 in Document 2 below), and Jordan is even primarily responsible for the security in Jordan outside the USA’s facilities (see Clause 4 in Document 2 below), so the USA has no any commitment to defend Jordan in the case of an attack. Hence, paradoxically, during the last years, not only that Jordan not have more security, but the opposite, Jordan suffered from attacks against the USA’s bases and installations in Jordan (Cite 9). Even Qatar suffered a retaliation attack from Iran against the USA military base in Qatar following the USA attack against the nuclear sites in Iran (Cite 10). Thus, Qatar unintentionally suffered from indirect involvement in the 12 Days War between Iran and Israel, only because that Qatar has a USA military base in its territory, which gives an indication about the Military Risk due to Foreign Military Presence, from the Host Country perspective.

Even from the Home Country perspective, exists a Trade-Off between the Military Benefits and the Military Risks regarding Foreign Military Presence. On the one hand, Foreign Military Presence gives the home country strategic military points around the world, especially if it implemented a policy of ‘Military Imperialism’ as in the case of the USA in which it has numerous host countries with Foreign Military Presence (see Chart 18 below). On the other hand, if the home country has too many host countries with Foreign Military Presence, then it burdens heavily on the home country in terms of military spending and the dispersion of the military capabilities because of the need to handle in parallel too many foreign military bases and installations in host countries, which significantly increases the military risk of the home country, especially if the home country also has colonies with military bases. Moreover, the desire to have military strategic locations worldwide has led to a trend of 'Rental land' for Military Bases without any Military Cooperation with the ‘Landlord’. For example, Djibouti has become an attractive location for foreign Military Bases because of its strategic location at the entrance of the Red Sea, so several foreign military bases were established in Djibouti under a high-cost rental contract (Cite 11), yet most of them are without any Military Cooperation with the government of Djibouti. Considering the above, the 2025 Global Survival Rank (GSR) takes into account the Foreign Military Presence in host countries, especially regarding the Military Risk of the home country because of the need of the Home Country to ‘protect’ multiple military facilities and personnel in distant countries.

Document 2. Article 6 on Security From the USA-Jordan Defense Cooperation Agreement about the USA’s Foreign Military Presence in Jordan

For Full Agreement, please see https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/21-317-Jordan-Defense-DCA-01.31.2021-with-Exchange-of-Notes.pdf

Chart 17. Foreign Military Presence by Region, Total Number of Foreign Military Bases and Installations per Region

Chart 18. Home Country Perspective: Number of Host Countries that the Home Country has with Foreign Military Presence

Cite 8. Are there any U.S. military bases in Jordan?, TheGunZone, 24 May 2024

Cite 9. What to know about Tower 22, the US base in Jordan struck in deadly drone attack, abc news, 30 January 2024

Cite 10. Iran strikes US base in Qatar; Trump says Israel-Iran ceasefire coming, Fox6, 23 June 2025

Cite 11. Why Is Djibouti, the Tiny African Nation, Hosting the World’s Superpower Military Bases?, Diplomatic Watch, 26 January 2025